Richard Butler played the role of Johnathan Harker in the 1951 British revival tour of Dracula. Apart from a two-week break when he had to do military reserve training, he was with the tour for its whole six months, acting opposite Bela Lugosi in 210 performances. I interviewed Richard on July 4, 1996, at the National Theatre in London while researching Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi In Britain.

Richard as the vicar who conducts the fourth wedding in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

Richard as the vicar who conducts the fourth wedding in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

Richard began his acting career at the age of 12 in a stage version of Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley in his native Yorkshire. He went on to enjoy a long and varied career on stage, screen and TV. His impressive list of theatre credits include a West End revival and touring production of Charley’s Aunt and A Provincial Life opposite Anthony Hopkins at the Royal Court Theatre. In early 1951, however, he found himself “resting.” It was a tough period for theatrical actors in Britain. Post-war austerity and competition for audiences from TV and the Festival of Britain, a national exhibition to promote the British contribution to science, technology and the arts, left theatres half empty and led to plays which had been expected to succeed to fold. Richard supported himself as best he could while waiting for a call from his agent:

Andi Brooks: How did you get the role of Jonathan Harker in Dracula?

Richard Butler: I was simply called by my agent to go for an audition. I went and I got it. At the time I was doing a stint at Walls’ Ice Cream factory in Acton, a temporary job, to earn some money. I remember going from my night shift to this audition and I got the job. But it wasn’t due to start for another couple of weeks so I stayed on, very nobly stayed on, at the ice cream factory, knee-deep in ice cream for another two weeks and (laughing) I’ve never been back to an ice cream factory.

AB: Was it an exciting prospect to be playing with Bela?

RB: Oh yes, because, let’s face it, I was in the ice cream factory. Although I had done an awful lot before I went there, it was one of those long periods of unemployment that all actors have. I’d done better work, much better work, than Dracula, but I took the job because it paid money. I’d much rather work than not work.

AB: Were you familiar with Bela’s films or the novel?

RB: Yes, the films, I certainly was. I’d seen Ninotchka then, you must have seen it? I think he’s marvellous in that, that’s the true Bela. I don’t think that I was terribly familiar with the novel, but, you know, one sort of knew it.

AB: How long did you have to rehearse before Bela arrived from America?

RB: He came there at once! We probably didn’t rehearse more than…certainly no more than three weeks. We might have rehearsed for as little as two weeks, but I really can’t remember.

(Ed: The company rehearsed for two weeks, beginning on April 16th in London and finishing with a dress rehearsal on April 29th at the Theatre Royal in Brighton)

AB: Do you recall where rehearsals took place?

RB: They took place in London, though I’m not certain of the exact location. It would certainly have been in the West End. I have an idea it was somewhere near the Embankment in Chelsea.

(Ed: Rehearsals took place in a banquet room above an unidentified pub in Pont Street in South Kensington in London from April 16th – 22nd. They then moved to the Duke of York’s Theatre in the West End from April 23rd – 28th. The dress rehearsal took place at the Theatre Royal in Brighton on April 29th, the day before the premiere.)

AB: It has been claimed that Bela was so unhappy with the production that the premiere was held up because he demanded changes.

RB: I don’t think that happened. He was never disloyal to the management. He never said “Oh, this shouldn’t happen to me at my time of life,” nothing like that. He just accepted things, and he really did his very best. I’ve worked with people who haven’t really done their best at every performance because it’s been a matinée or there have been few people in, things like that. But he had the very highest standards. Bela kept his dignity throughout and never criticised or complained. I do, however, remember that, talking to us youngsters during rehearsal break one day, he said—“I’m over here to do this show because I can’t get work in films these days. Some time ago, both Boris Karloff and I realized the skids were under us…so we take what work we can get.” We were visited at the dress rehearsal and first night by Megs Jenkins, a very well-known actress. She gave invaluable help to Sheila Wynn with her hair-do, make-up and costume. We had no wardrobe mistress as far as I can remember, and we had to fend for ourselves. Megs Jenkins, incidentally, was married to George Routledge of Routledge & White, the management company that organized the tour. Some time later, he left her in the lurch, taking all her money.

AB: About the 1951 tour, a recent magazine article about Bela claims that (Andi reads) “the supporting cast smacked of poverty row…the rest of the cast, too inexperienced to do otherwise, had not mastered their lines.” What’s your reaction to his accusations?

RB: Absolute rubbish! Absolute rubbish! You write another article. That is utter rubbish. Bela was the only “name” in a cast of mainly young unknowns, but the whole cast was quite experienced. Arthur Hosking had been an established actor, especially in musicals, for many years. David Dawson had done television and was quite a presentable leading man. Sheila Wynn had done quite a bit of work, as had Joan Harding. I first came across Sheila in 1947 when she and I worked together. John Saunders had certainly done a lot of work. Who else was there? Oh, Eric Lindsay. Well, he had done work of a sort.

Richard as Braithwaite in the hit TV series Budgie (1971)

AB: What was the pay like for appearing in Dracula?

RB: I think I received about £12 per week. In those days £10 per week was considered a good salary in weekly repertoire, and one was always paid a little more for touring. But there was no such payment as a touring allowance then and rehearsals were unpaid for several years to come. At the time, actors were expected to provide every item of contemporary clothing, except for special items such as morning suits and uniforms and as a result, our wardrobes were somewhat depleted. I daresay David had his consultant’s morning clothes supplied, similarly John Saunders’ attendant’s uniform and perhaps Eric was helped with his Renfield clothes.

AB: The article is very critical of the sets.

RB: That’s true, they were very cheaply made. The backdrops and scenery were painted on cloth, very shabby. The special effects, flying bats and magical appearances by Dracula, were very rudimentary to say the least, and very unreliable. The bats were a particular problem. They would be catapulted across the stage, and often they wouldn’t make it and would land in the middle of the stage, where they would have to stay. In the climax of the short prologue to the play—which was a solo spot for Sheila, standing spotlit in front of black tabs, a large model bat on wires descended from the flies in a large cloud of smoke (fired from a smoke gun behind the tabs) and lowered over her head as she screamed. Immediate black-out, followed by the black tabs opening to reveal the brightly lit consulting room. I, as Jonathan Harker, then entered to await the imminent arrival of David Dawson. Invariably, there was a considerable amount of smoke—a cloud, in fact—still hanging over the stalls, which we had learned to live with, but on one dreadful occasion the model bat was also present; its wires having jammed, suspended over David’s desk between his chair and the chair I was about to occupy. I steeled myself for the ordeal to come and resolved to suppress my inner hysteria. I remember wondering how and if David and I should refer to it in any way, but decided that we had best ignore it! David entered, saw the bat, of course, and we both knew instinctively that eye contact between us must be avoided for the scene to continue. When we took our seats the bat was dangling between us at eye level—it was quite a sizeable object! So, we proceeded to ignore it and each other, and spoke our lines directly to the audience. My firm resolve was shattered when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw David gently easing the bat to one side in order to see me, but with a great effort of will we both managed to keep talking. There wasn’t a titter nor any response from the audience to indicate they were aware that anything was amiss, and in some strange way this helped us. We battled on, but when, a short time later, the bat’s wires were sorted out and it suddenly shot up into the flies and out of sight, I’m afraid we were both quite helpless with laughter. Disgraceful behaviour on our part, but I think you’ll agree we were sorely tried.

AB: It’s strange that all the people whom I have spoken who saw the play were particularly impressed with the special effects.

RB: Really? That is strange.

AB: Did Bela ever offer advice as to how the rest of the cast should play their roles?

RB: Only once. After our first night in Brighton, Bela met me in the wings one night after I had played my first scene with Lucy, who in the play has been visited by Count Dracula and somehow indoctrinated into vampirism. This was all unbeknownst to me, her fiancé, who is visiting her, as she recovers from the vampire attack. During the scene I express my worries and fears for her safety, and she gradually gets the urge to sink her teeth into my neck. Horror stations! And a merciful black-out ended the scene. Bela said to me, “I think you could get more out of that scene. Would you mind if I rehearsed it with you both?” This was music to my ears as our director, who was memorable for his fancy socks, had left us immediately after our first performance with a single note, which is not unusual, even today, and there would have been inevitably much in the production which could have been improved. Well, Sheila and I were re-rehearsed by Bela and whatever he did in the way of re-directing us must have helped because after we had played the scene as directed by him, he had watched us from the wings, he put his hands on my shoulders and kissed me on both cheeks in the continental manner. “That was much better,” he said, and referring to the kisses, “and I am not a fairy!!” That’s the only time he did something off his own back, and I was only too grateful.

Bela, Arthur Hosking (Van Helsing), Richard and David Dawson (Dr. Seward)

AB: What did you think of Bela as an actor?

RB: Oh, I thought he was first class. He had height and a stunning presence, no excess weight. He had saturnine looks, and his greatest asset of all, a superb voice. On stage this was produced so effortlessly. He could speak in a seeming menacing whisper at, say, The Hippodrome, Golders Green, and be heard at the back of the gallery. This is before the introduction of microphones on stage—a terrible practice! That’s what surprised everyone, that he was such a wonderful stage actor. You get many people, like Olivier or instance, who give out when they’re on, but don’t give out so much when they’re off, but he (Bela) wasn’t a nonentity off stage.

AB: How did you find him as a person?

RB: Both he and Lillian were charming and very accessible. He was instantly friendly, but he was treated with all due deference because he was a movie star, and he was the reason that we were doing that play. There was an atmosphere of great courtesy on both sides. We called him “Bela”, we asked if he minded, Lillian said, “Sure, sure go ahead.”

AB: What was life like on the road with the Lugosis?

RB: This was in the days when the pecking order in any theatrical company, be it in the West End, number one, two or three tour and some repertory theatres, was always strictly adhered to. In those days on tour when theatre dates were rarely longer than a week in any given place, companies travelled by train. The Lugosis certainly travelled with the company, though they might have a car from time to time. I sometimes travelled with John Saunders by car—as far as I can remember he was the only car owner in the company. Train calls on a Sunday morning meant assembling at the local station where the manager would assign company members to their respective carriages, which were reserved. We never travelled with the general public. There was a strict order of precedence observed, the leading members of the company travelling together, the supporting featured players—according to salary—then the rest of the actors—small parts and understudies—and the staff wardrobe mistress, carpenter, often a married pair—and the stage management in separate compartments—not with the actors. That was the start of the journey, and discrete mingling took place as the train progressed. All the Sunday papers were bought—sharing took place, of course—and, if the journey happened to be a long one, food and drink had to be bought by individuals on Saturday night as trains in those days, especially on Sunday, rarely had buffet or restaurant cars, and intermediate stops at stations en route couldn’t be relied upon to provide a buffet that would be open. Now in Bela’s case, although he and his wife had their own compartment, they had no wish to travel alone and spent many hours entertaining us. Except, that was, on certain occasions, when Lillian would say, “Now Bela has to have his injection.” That was our cue to leave. At that time Lillian had indicated that Bela had a health problem which necessitated medication, and it wasn’t until much later, after they had returned to America and poor Bela’s drug use became known, that we wondered if his “health problem” had been, in fact, his drug addiction.

AB: He committed himself to cure his addiction, apparently he had been suffering from leg pains for many years.

RB: I can remember that foot problem that he had. I can see him now, but I had to be reminded of it. Perhaps that is why he didn’t walk around? You rarely saw him except during the play. We never met him or Lillian around the town where we happened to be. He just didn’t go out. Wherever we happened to be, in England or Scotland, he knew nothing about the particular city or area, nor did he express any interest in local sights or places of interest. A car picked him up from his hotel and a car collected him from the stage door. Perhaps that’s why he didn’t walk around, he was just afraid of something happening. We didn’t even go out with Lillian, but maybe he was jealous? Maybe she wouldn’t have dreamt of saying, “Come on, boys, take me to the cathedral or take me to the pictures.”

AB: I don’t think he would have liked that.

RB: No, he wouldn’t. But he always welcomed us into his dressing room, there was never any suggestion that we weren’t welcome. From the beginning of the tour Bela’s No. 1 dressing room, wherever we played, was open house to us all, and coffee, beautiful American coffee, seemed to be always on tap, thanks to Lillian.

AB: Did the cast ever go back to his hotel after the show?

RB: No, there was no socializing after the show at all. It was before and during, but not after. Bela and Lillian always stayed in hotels during the tour, the rest of us stayed in “theatrical digs,” which in those days were still plentiful. These digs differed from ordinary lodging houses in that, in most cases, all meals were provided and geared to an actor’ working day—late breakfast and late cooked suppers after the show. Stage door keepers almost always had lists of available digs, and one could write to them in advance for recommendations. But almost all actors had their own digs address books and, as a rule, if one didn’t have an address for a future date, one consulted friends or other members of the company. The aim was to book in advance, seasonal actors often had the tour booked before the first train call—and never, if at all possible, to arrive at a new date with no address fixed. Of course, there were bad digs, too, and actors made careful notes of addresses to avoid and warned other actors about them if at all possible.

AB: Do you recall any particular incidents during the tour?

RB: Bela was always charming to us backstage, and his interest in our somewhat second-rate production never flagged. Needless to say, his own performance was always full throttle and the customers were enthralled. Save, that is, at one theatre—the Golders Green Hippodrome—where to our amazement, we got the bird. Any references to crucifixes, and there are many in the play, were greeted with cries of derision, and our crude special effects called forth hoots of laughter. Perhaps, if Count Dracula had spent longer on the stage the unruly audience would have been more amenable. It was the American version of the play, his part was extremely short. His short scenes amounted to no more than 20 minutes of the total two hours running time, but his appearances were so impressive that no one complained of being short-changed. In one theatre, the Lewisham Hippodrome where we were playing twice nightly, we were given a rough ride. But this was entirely a management error. On the first night of our one-week run our Van Helsing (Arthur Hosking), by far the largest part in the play, was indisposed. His part was taken by a dear old character actor, Alfred Beale. “Bealey”, as we called him, was actually our business manager. I thought he was a saint. He had been an actor, but I don’t think he had exercised his craft for many years. The management error was in expecting this man to go on in a leading part without the benefit of a single rehearsal. Mrs. Beale was very concerned about him, and came down to give him help and support. Bela was most concerned for him. I remember the scene on stage before the curtain went up on Van Helsing’s first appearance. There was Bealey with his script in his hands, the poor man had to read the part, and at his side was Bela with benzedrine in tablet form and a large jug of water. This had an immediate effect on Bealey and after the curtain rose he appeared not to have a care in the world as he read from his script. This was much to the audience’s displeasure and, I’m sorry to say, our hard-to-suppress amusement. I had to make an appearance in the scene, and my entrance coincided with Bealey dropping his script, which was not stapled but loose-leafed. Mrs. Beale was in the fireplace, attempting to bring poor old Bealey back onto the script, and as he skipped about the stage picking up the scattered pages, still not panicked by the laughter and shouts from the auditorium, we had to end the scene as best we could, though we were not nearly as mirthful as we had been at the start. Arthur Hosking rejoined us for the next performance. I’ll tell you one funny thing that happened. We thought that we were going to have a riot in Scotland because the playbill announced, “First Time in England.” Even then the Scottish Nationalists were around, and I thought we were going to have a bomb-attack or something. They never changed it. I laughed like a drake when I saw that, “First Time in England.”

Richard and Hugh Grant in Four Weddings and a Funeral

AB: Could the play ever have really succeeded in the West End?

RB: No, it would have flopped definitely. It was such a tatty production.

AB: Could more money have turned it into a success?

RB: Not with that management. They obviously didn’t have the right standards. Out of their hands, who knows what might have happened? But by then it was a bit of a freak show. No, it wouldn’t have lasted more than two minutes.

AB: That was Bela’s whole reason for coming to Britain—he thought that he would be playing in the West End.

RB: Yes, maybe. People have lied before. That was a lying management if ever there was one.

AB: Was there any advance warning that the tour was in trouble?

RB: We got a fortnight’s notice. They had to do that or they would have had to pay us two weeks wages, and they wouldn’t have done that. Yes, we had due warning.

(Ed: The tour ended at Bela’s request. Although further dates near Newcastle and Liverpool had been lined-up by producer John C. Mather, it was clear that the production was unlikely to ever reach the West End as intended. Bela was exhausted by the tour’s punishing schedule. When John told Bela that they had to play the proposed new dates if the tour was to continue, Bela replied, “John, I can’t go on, it’s taking too much out of me. Please finish it quickly.” The production took a two-week break before fulfilling its final contracted run at the Theatre Royal in Portsmouth from October 8th – 13th.)

AB: So you were all paid?

RB: We were paid, the actors. I don’t know about the others.

AB: It has always been claimed that Bela wasn’t paid, that he and Lillian were stranded in Britain, that’s why he appeared in the Mother Riley film.

RB: It could just be another story, an excuse for him appearing in such a poor film. I imagine it was. He never said anything, and Lillian never said to us, “Oh, they haven’t paid Bela.” I think they just slotted Bela into the film. They were just opportunistic. As you said, it was already set up, it just suited everybody, Bela and Lillian. John Saunders, sadly no longer with us, and I were friends on the tour. He played the least rewarding part in the piece, the asylum attendant. He and I were especially friendly with Lillian. We were all interested in food and cooking—what actor isn’t? As the tour was drawing to its end Lillian said, “You must visit us one evening and I’ll cook you an American corned-beef hash.” At this point Bela had already booked to play in the film, and he and Lillian had rented a house near the studio. She was as good as her word. One day, John drove us out to their house, he was the only car owner in the company, and sure enough, in their kitchen we sat down to a delicious meal while Bela and Lillian regaled us with red-hot gossip from the studios. He spoke with a heavy but perfectly understandable accent, with many Americanisms. I particularly remember tulips pronounced “toolips”.

(Ed: Despite the still persisting legend that Bela’s appearance in Mother Riley Meets the Vampire was hastily arranged to provide money to pay for his passage back to America after he and Lillian were left stranded in England when the tour collapsed after a few disastrous performances, his involvement in the film was first announced in the August 9th issue of Kinematography Weekly – three months before filming began, and two months before the tour ended.)

Richard, Anthony Hopkins, Shivaun O’Casey, and Geoffrey Whitehead rehearsing for A Provincial Life at the Royal Court Theatre in 1966

After Dracula Richard became an in-demand actor for over 40 years. He made his debut television appearance in 1952. In 1959, as Lugosi’s phantom film Lock Up Your Daughters briefly materialized, Richard did a long stint in a play of the same name on the West End. He appeared in many television series and mini-series, such as Coronation Street and Middlemarch, and played the vicar who conducts the fourth wedding in Four Weddings & A Funeral. In October 1982 Richard was guest of honor at the Dracula Society of London’s celebration of the centennial of Bela’s birth and spoke publicly for the first time about working in Dracula. Richard died in early 2004.

—————————–

Related pages and articles

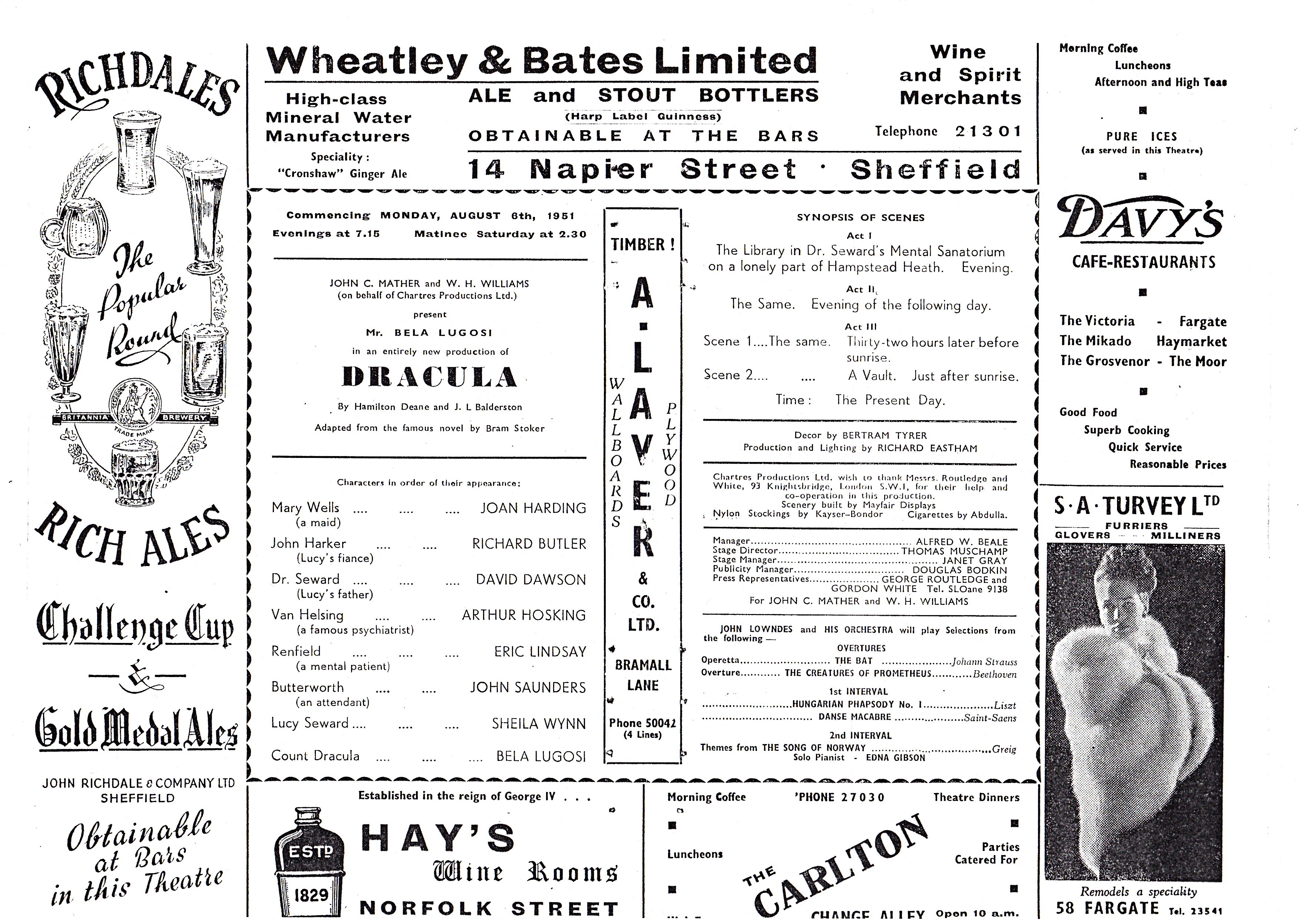

1951 British Dracula Tour – Newspaper Articles And Memorabilia

1951 British Dracula Tour – Exclusive Interviews With The Cast & Company

From A To Zee: Eric Lindsay, Bela Lugosi’s Last Renfield

An Encounter With Bela Lugosi by Roy Tomlinson

Mother Riley Meets The Vampire

“Mother Riley Meets The Vampire” Robot Fails To Sell At Auction

The Return Of The “Mother Riley Meets The Vampire” Robot

Richard as the vicar who conducts the fourth wedding in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

Richard as the vicar who conducts the fourth wedding in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)