Bela and Beatrice on their wedding day

In late July 1929, Bela Lugosi arrived in San Francisco with a touring company of Dracula. Within 10 days he wed and separated from Beatrice Weeks. The Weeks‑Lugosi marriage has all the credentials of a wild fling from the Roaring 20’s: she a wealthy, widowed heiress; he a rising stage and screen star. Both marrying for the third time; both living life to its fullest. Lugosi breezed into town, and breezed out never to see his bride again. She hopped over to Reno and filed for “incompatibility.” Their divorce was final in December. The tabloids picked up the story, linked the break-up of the newlyweds to screen siren Clara Bow, an easy target for the scandal sheets.

Lives cannot be told from news clippings, but Beatrice Weeks’ may have left no other trace. Any biography of her is filled with “probably” and “may have.” The press clippings tell a depressing tale, one that can be documented today only because the four men in her life each achieved prominence. Beneath the glitter of her showbiz style marriage to Lugosi lurks the sobering tale of a woman slipping from desperation to destruction.

Weeks and Bow are minor but pivotal figures in the Lugosi legend. His marriage to Weeks and his torrid affair with Clara Bow (all Bow’s affairs are described as “torrid”) prove that the commanding, caped figure once cast spells over women. Weeks and Bow were both financially independent, quite younger than he and first saw him in an audience watching Dracula. The sexual element in the Lugosi mystique wears a bit thin with time, and without it Lugosi is less a prince of darkness and more a high lord of camp. But in his prime in the 1920’s—before the movies had influenced our view of the man and the actor—Lugosi was reaching across the footlights to sweep young women of position and means off their feet. Dracula himself could have done no better.

Of course, that is the stuff of legend. In fact the Weeks-Lugosi marriage was not the impulsive event invented by myth. Their intentions were announced at least 3 days before the wedding. By then the couple had known each other for about a year, during which, if Lugosi is to be believed, they had been in frequent contact. Lugosi was hardly a rising star. When he married this rich, young widow, his film career had stalled. He joined the Dracula tour out of necessity. His limited English and thick accent made finding roles in early sound films difficult. Not until after the marriage ended did he start regularly landing character parts. Dracula was not filmed until a year later.

A “Torrid Affair” with Clara Bow?

Clara Bow

Not much is reliably known of Lugosi’s famous fling with screen siren Clara Bow—famous because a tryst with “Dracula” adds some spice and variety to Bow’s legendary promiscuity. The activities of Bow, voted most popular screen star about the time she met Lugosi, supplied gossip columns with juicy stories throughout her brief career. Her legend took final form in 1931 when Bow’s secretary Daisy DeVoe sold her recollections to The New York Evening Graphic. DeVoe, then charged and later convicted of embezzling from Bow, trashed her former boss and cited every man Bow ever knew, including Lugosi, as her lover. Given Bow’s reputation, no one doubted DeVoe. The Graphic, the most sordid of tabloids, was published for only eight years, and very few libraries archived it. Literally every copy carrying the DeVoe revelations has been stolen from those archives, and documenting today what DeVoe actually said is all but impossible. Apparently, she only included Lugosi’s name in a long list Bow’s conquests. The Bow-Lugosi affair is dutifully mentioned in every Lugosi biography, every Bow biography, most biographies of any of Bow’s lovers (notably Gary Cooper), as well as in such books as Hollywood Babylon. Dracula-Meets-The-It-Girl is just too juicy for authors to ignore.

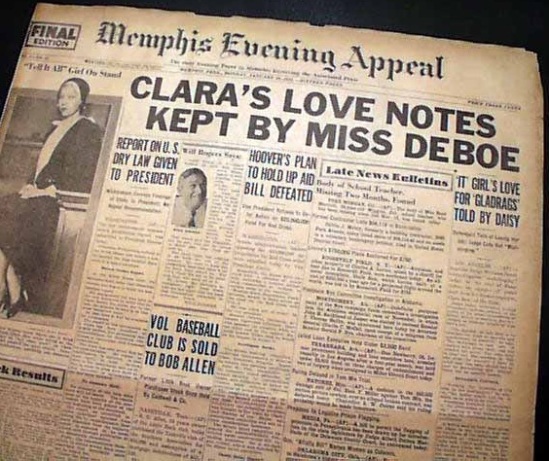

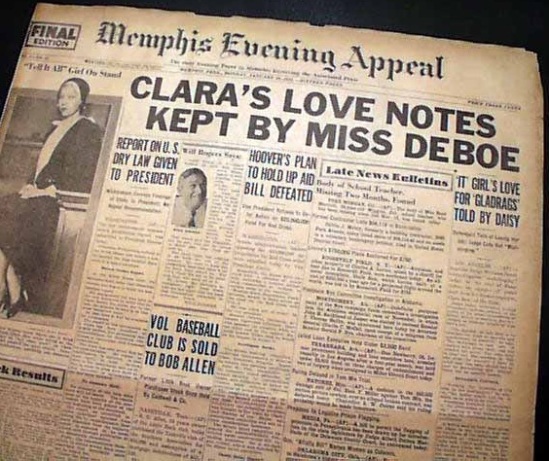

Memphis Evening Appeal, January 17, 1931

Lugosi’s and Bow’s first meeting can be reliably dated. Dracula closed on Broadway on May 19, 1928, and opened with much of the Broadway cast in Los Angeles on June 24, 1928 for an eight-week run. The play received a press ballyhoo that it never got in New York, and Lugosi quickly became a much talked-about celebrity. Hollywood was then beginning the conversion from silent to sound films—an upheaval dreaded by many performers who had no experience with dialogue. Clara Bow, whose voice no audience had yet heard, was particularly intrigued by publicity claims that Lugosi learned his lines phonetically. Bow’s friend, comedian and comic character actor Jack Oakie, recalls in his light-hearted autobiography (Jack Oakie’s Double Takes) Bow’s first meeting with Lugosi:

Suddenly she came running out (to her swimming pool, where she had left friends to take a phone call). “Come on everybody! We’ve got tickets!” she said. “We’re going down to the Biltmore to see Dracula.” She was so excited she didn’t stop to dress. She just threw a great long mink coat over her swimsuit, and we all got into her chauffeur-driven black Packard limousine. Bela Lugosi was starring in Dracula on the stage of the Biltmore Theatre downtown.

Bow had read about it. “I want to meet that man,” she said. “Do you know he doesn’t know how to speak English.” She couldn’t get over the fact that he was on stage for two hours performing in a language he couldn’t speak. Bow kept her mink coat on, and we watched Bela Lugosi in his monstrous makeup with his teeth sticking out, chewing on gals’ necks all evening. Then we went backstage.

He couldn’t speak English, but no language barrier could hide his thrill at meeting Clara Bow. He was overwhelmed with the redhead. “How do you know your lines?” Bow asked him immediately. We finally understood the Hungarian’s explanation. He told us that he memorized each word from a cue and, if by mistake another actor should ever give him a wrong line, he would be lost for the rest of the night. Bow invited him to her home, and they became very good friends.

Bela poses at home beneath a nude portrait of Clara in the early 1930s

Lugosi probably exaggerated his language difficulties for Bow’s benefit, for he was more proficient in conversational English than he let on. Horror film producer William Castle relates in his autobiography that, as 14 year-old Bill Schloss from Brooklyn, he met Lugosi in New York in 1927 and conversed well enough with him. Throughout the Los Angeles run of Dracula Lugosi was interviewed by the papers constantly, and handled questions with some aplomb. When The Los Angeles Examiner asked if he was a bachelor, Lugosi responded, “Oh, surely, madame. And ‘open for business,’ you think, yes?”

When Clara met Lugosi in 1928, she was moreorless between great romances. Her typically “torrid affair” with Gary Cooper had just ended, and a romance of allegedly equal passion and abandon with Broadway singer Harry Richman had not yet begun. Though Cooper would be one of her great loves, she certainly had others during 1926 and 1927 when their romance peaked. By 1928 each had moved on, but the two were occasionally seen together, as both juggled multiple lovers. Though Clara openly prized her freedom, the press often carried announcements of her engagements and pending marriages. These abound for Cooper and Richman, but neither was true. Nor were they true for Lugosi, when those same rumors started in 1929, probably long after whatever relationship they had ended. Lugosi’s film career struggled through 1928 and 1929. The simple fact he never appeared in a Bow film or at her studio (Paramount) suggests the limitations on their fling. Bow was never shy about using her influence to land her lovers roles, with or without their knowledge. Gorgeous, carefree, age 23 and definitely not in the market for a husband or even a regular lover, she constantly surrounded herself with friends and hangers-on. On one weekend (according to David Stenn’s biography Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild), Lugosi arrived at her Malibu cottage only to find every bedroom occupied by guests. One gave her room to Lugosi and moved in with Bow.

About the time Lugosi met Bow, her brief stardom had crested. Scandal, her own fragile health, and sound films (she had a wonderful Brooklyn accent) brought her downfall. By 1931 her career was in ruins and by 1933 she had made her last film. Lugosi apparently retained affection for this unpretentious, generous woman, for he kept a tasteful nude painting of her until he died. What sort of relationship Lugosi maintained with Bow beyond his two-month engagement at the Biltmore is unknown. In August 1928 Dracula and Lugosi moved on to San Francisco.

Beatrice Woodruff, Beatrice Mills, Beatrice Weeks

Beatrice Weeks

Beatrice Woodruff was born in 1897 in New York City. Her father, John S. Woodruff graduated from Harvard shortly before her birth, and soon afterwards entered a career in naval law. He eventually became Director of the Bureau of Law of the United States Shipping Board. Through her mother, Marion Parker, Beatrice could trace her lineage back to the Pilgrims. As befitting a young woman of her rank, she attended the exclusive Wellesley school and a European finishing school. There, she developed a proficiency in foreign languages.

In 1921 she married Goadby Mills, son of a prominent New York stockbroker. Immediately following their large, elaborate ceremony, Mills told his bride, 20 years his junior, “Now we are married and the main point is that you are legally mine.” In the succeeding weeks Mills proved his claim. After 57 days Beatrice could stand no more and the two separated. Mills died 10 years later in a plane crash.

New York Evening Telegram, January 11, 1920

In January 1922, Beatrice filed for divorced in Los Angeles on the grounds of cruelty. She may have gone from New York to the West Coast because she was already developing health problems, and needed milder winters. In California she met Charles Peter Weeks, a San Francisco architect of local notoriety. Mills had lived in his father’s shadow and off his wealth, but Weeks was a self‑made man. His firm, Weeks and Day (presumably no pun intended), built many of the finest structures of San Francisco’s post‑earthquake renaissance. He designed a number of fashionable homes, apartment buildings and hotels on Nob Hill. About the time he met Beatrice he was caught in the roguish position of admitting that a magnificent golden staircase in an office building he had just completed was an unaccredited duplicate of that in the Borgos Cathedral. His romance with the still‑married Beatrice raised eyebrows in the society circles into which he had risen. On January 30, 1923—one day after her divorce from Mills was final—Beatrice, age 25, married Weeks, age 45. She chose not to relive any moments from her first marriage; this time the ceremony was quite modest.

Nothing is known of Beatrice Weeks’ life for the next five years. She and her husband settled into the Brocklebank Apartments, which Weeks had designed. Their contentment collapsed in March 1928. Pulmonary disease, which would plague her for the remainder of her life, struck Beatrice at age 31. As she hovered near death, Weeks died without warning in his sleep on March 25. His death was ascribed to “a malady from which he had been suffering for a number of years and for which he had been under the care of a physician for many months.” He died in the room next to Beatrice, but she was not told of his death until sometimes afterwards.

That Beatrice ever fully recovered from the ordeal is doubtful. The unexpected death of her father at age 58 in January 1929 caused yet another setback. Perhaps the only bright spot for her in these tragic months involved a handsome, exotic actor in the summer of 1928.

Bela and Beatrice with an unidentified friend

The First Meeting in 1928

The touring company of Dracula arrived in San Francisco in mid‑August 1928 for a three-week run. The troupe booked into the Mark Hopkins Hotel, just a short walk from the Columbia theatre and, incidentally, one of Weeks’ architectural masterpieces. Dracula opened on the 20th to rave reviews, and its star soon became a celebrity throughout the Bay Area. Bela Lugosi at 46 was at the height of his powers. Commanding and aristocratic in presence, riding success as Dracula, he was finally poised to claim the stardom that world war and political upheaval had denied him in Hungary.

Shortly after the San Francisco premiere of Dracula, Lugosi attended a reception at Mare Island, and met a shapely, raven‑haired woman. The party was perhaps Beatrice Weeks’ first outing since her near‑fatal illness and the death of husband five months before. She and Lugosi struck up a quick friendship and became constant companions for the remainder of Dracula’s run in San Francisco and then Oakland. When Lugosi returned to Hollywood in late September, the two wrote and stayed in touch.

Lugosi still commanded the striking good looks of his youth, and American women found his old world mien irresistible. Weeks herself was a stunning beauty. History has played a cruel joke in that the only photograph of Beatrice Weeks seen today is singularly unflattering. In this photo, which appears in every Lugosi biography, she and Lugosi seem to be comparing their large noses. As a good many photos in San Francisco newspapers testify, she was quite attractive.

At 31 Beatrice was wealthy, beautiful and quite alone. Her lung condition left her with the lingering prospect of early death. That question must have haunted her through 1928 and 1929 and the successive deaths of her husband and father. Now to her came a worldly foreigner who had survived several close brushes with death, and who was famous in a role as lord of the undead. Goadby Mills, Charles Weeks and now Bela Lugosi all were in their mid‑forties when their romances with Beatrice began; all were well‑known in their professional and social circles; all three can be surmised to have been men of strong and dominant personalities. These similarities beg the question—was Beatrice marrying the same man time and again? Was her father—Harvard lawyer, naval officer and Washington bureaucrat—the prototype for Beatrice’s three husbands?

Much the same can be asked of Lugosi. Beneath his self‑assured exterior must have lurked a man daunted by his new surroundings. He no doubt hoped to pool Dracula into a film career, but the advent of sound films stalled his progress. The thick Lugosi accent and the crude sound equipment were simply not ready for each other. Shortly after his arrival in Los Angeles in June 1928, he was whisked off to a screen test with Gloria Swanson. He did not get the part, not due to his English, but because unlike most actors in Hollywood claiming to be over 6 feet tall, Lugosi actually was. Swanson, at 5’1”, disappeared when next to him. Surely, by the time he first met Weeks, he had learned—as in the past 15 years he had learnt on the Italian front, in post‑war Europe, and in New York—that Hollywood was yet another jungle with its own laws of survival. One of those laws was the worship of youth, and Lugosi was pushing 50. Another creeping notion was worrying him: in 1928, two years before filming Dracula, he was already complaining that American acting relied too much on typecasting and that he was playing the same type of role too often.

The Woman in Hungary, The Widow in California

When Lugosi fled Hungary in 1919, his sheltered wife Ilona did not follow. Both the Cremer and Lennig Lugosi biographies testify that he loved his young bride very much. The suggestive evidence that he never forgot her, that he was haunted by that loss, is considerable. In speaking of life in Hungary to interviewers, Lugosi would sometimes indulge in the most incredible fantasies. He told of an encounter with a female vampire; he conjured up the famous story of Hedy the Cat Woman; he claimed he deserted not only a wife but also sons in Hungary. For two decades he whimsically doled out variations of these tales to eager journalists and publicists. The one consistent element in all of them is the Woman in Hungary.

In America, Lugosi’s wives would be either very young, very Hungarian or both. His second wife, Ilona von Montagh, was Hungarian and 20 years younger. Beatrice, his third, was his junior by 15 years; Hope Lininger, his fifth, by 32. His fourth and only marriage of any duration was to Lillian Arch, 30 years younger and a second generation Hungarian‑American. She states in Cremer’s biography:

Yes, that was the reason why he married me. I was a person he could mould to his complete satisfaction.

Lugosi’s memory of Ilona crept into at least one of his film roles. In 1934’s The Black Cat, Vitus Werdegast returns to Hungary after 15 years in prison to find his lost bride and daughter and to kill the man who took them from him. He finds his wife unchanged—dead and encased in glass. His daughter, her mother’s image, is killed before Werdegast can reach her. He weeps over her body before taking his revenge. Werdegast’s plight is a morbid distortion of Lugosi’s own. This incredible film is almost a dark biography of the actor—the lost love in Hungary, the upheaval of world war, years of exile, and the evils of the new world personified by Boris Karloff.

Reclaiming a young, unspoilt love is a common male fantasy, and a familiar element in horror plots. The fantasy dogged Lugosi, most clearly in The Raven, The Corpse Vanishes, The Invisible Ghost, Voodoo Man, and his soliloquy in Bride of the Monster. Of course to suggest that the theme’s relation to Lugosi’s own life was intentional in any films other than The Black Cat is absurd. But the list contains his most personal performance, his most passionate, the best of his poverty row films and a surprisingly poignant moment in an otherwise awful Ed Wood film.

In Beatrice, Lugosi might well have seen a clear reflection of his first Ilona. Both came from social classes above his. Despite their financial means, both were in need of a strong man. When he last saw Ilona and when he first met Beatrice a distinct air of tragedy hovered over them.

The Whirlwind Marriage and Divorce of 1929

According to interviews Lugosi gave when they married, he and Weeks corresponded after parting in October 1928. Lugosi may not yet have been able to write well in English, and Beatrice’s competence in languages perhaps served the romance well. The news they related in these letters, none of which are known to survive, could not have been very cheerful. Beatrice lost her father; and Lugosi’s career went nowhere. His only film role of note was in The Thirteenth Chair. In the summer of 1929 Lugosi accepted the lead in a West Coast touring company of Dracula. The production opened in Los Angeles to poor reviews, not surprising since it lacked of the polish of the Broadway production that had come west only a year before. The play then toured the Pacific Northwest without Lugosi, who remained in Hollywood for some film work. In July Lugosi rejoined the company in San Francisco. He and Weeks were reunited.

San Francisco Examiner, July 22, 1929

Dracula reopened at the Columbia Theatre on July 22, 1929. A notice appeared in the July 24 San Francisco Chronicle, announcing Beatrice’s and Lugosi’s impending wedding for Saturday, July 27. The marriage therefore was not the unplanned affair as it has been often described. According to The Chronicle, after meeting again “both decided nothing but marriage could make them happy.” The couple and a few of the bride’s friends went to Redwood City on the morning of the 27th, and returned in time for a matinée performance of Dracula.

At the Columbia a reporter from The San Francisco Examiner caught up with Lugosi. The actor, joking about the impossibility of hiding from the American press, was in rare form:

Examiner: Is she a blonde or a brunette?

Lugosi: Ooooooooo, I do not know.

Examiner: You do not know?

Lugosi: No. You see, it is like this. The eyes got in the way. You understand.

The interview ended with a remark by Lugosi quite out of context that must have sent shivers through Beatrice Lugosi when she read it:

Marriage and a career? No, the Hungarians believe that the man should take care of the woman. Her divine profession is motherhood.

That remark, of course, marked Lugosi’s unfailing transition from a passionate lover to a tyrannical husband. In marriage, Lugosi’s Hungarian upbringing with his quirks and insecurities. The result was jealousy and domination. Lugosi’s wives submitted, subverted, or left.

Beatrice and Lugosi separated approximately August 1. Beatrice left for Reno immediately, to satisfy the legal requirement of three months residence before a decree could be granted. Lugosi remained in the Bay Area for 5 weeks, playing 26 Dracula performances in San Francisco and then 20 more in Oakland.

Exactly what occurred during the couple’s brief time together is nowhere accurately recorded. Robert Cremer’sLugosi: The Man Behind the Cape describes the marriage as four days of drinking, partying, hangovers and bickering. Beatrice emerges as a Roaring 20’s socialite, living only for fun; Lugosi as a husband expecting a wife to cater to his mornings‑after and not vice versa. Cremer does not mention the prior meeting in 1928 or of Weeks’ background. Whether Cremer is quoting Lillian Lugosi or the Hungarian language newspaper, California Magyarsag, his ultimate source is Lugosi himself. Certainly to his Hungarian friends and particularly his next wife, Lugosi would tend to portray the Weeks marriage as a 4‑day fling and mistake, rather than a year‑long relationship. Cremer’s account is valuable in that relates how Lugosi chose to recall the marriage.

The break-up of the Lugosis might not have attracted much media attention—Lugosi was then only a minor celebrity—except the Hearst newspaper chain, based in San Francisco, sensed a good story. On November 5, 1929 The Daily Mirror, Hearst’s New York paper, ran this highly dramatized, inaccurate account, which dredges up Lugosi’s brief fling with Clara Bow:

Clara Bow

Lugosi Wins Heart of Clara Bow, Says Second Wife, Seeking Divorce.

Film Star’s Secret Love is Revealed

Clara Bow, flaming haired siren of the screen, has at last met with true romance–a romance, which ghost-like, sprang from the ashes of another woman’s love.

Folks, meet her fiancé and husband to-be; Count Bela Lugosi, Hungarian actor, the male vampire who took the leading role in the blood-curdling drama, “Dracula”.

Revelation of their secret love came exclusively to the Daily Mirror yesterday when Lugosi’s wife, the specially prominent, former Mrs. Charles Peter Weeks, widow of a noted San Francisco architect, filed suit for a divorce in Reno.

Simultaneously, the actual low-down on the Clara Bow-Harry Richman engagement was obtained from the same source.

Lugosi Returns

Clara, the impetuous, in a spirit of pique, caused the report of the forthcoming nuptials with the handsome night club entertainer to be spread after the long-haired Count Bela jilted her to become the third husband of the California society woman.

The fact that Count’s marriage resulted in a fiasco, lasting only four and one half days, apparently has appeased the feelings of the gay little screen star, and Lugosi has once more resumed his place in her affections.

“I don’t know when they will be married,” Mrs. Lugosi said. “But before I left my husband he told me he and Clara had been engaged; that they had agreed to remain away from each other a year to test their love.”

Lugosi’s ardent attachment for Miss Bow began shortly after he was divorced by his first wife, the former Ilona von Montagh, erstwhile musical comedy star, almost five years ago.

At that time the first Mrs. Lugosi, in gaining her freedom, denounced her married life with the noted Hungarian star, as “two months of boredom.”

Bela and Beatrice on their wedding day

He’s Heavy Lover

The Hungarian actor first gained the reputation as a heavy lover in this country, when, prior to his first marriage, he loved Estelle Winwood, in “Red Poppy”, so enthusiastically he cracked three of her ribs, causing her to retire from the cast.

Not at all loath to discuss her unhappy marital adventure with the foreign actor, the latest Mrs. Lugosi expressed no animosity to the youthful screen actress, whom she charges now holds the key to her husband’s heart.

Battle Starts Early

Lugosi fought the second day of their married life, his wife declared yesterday. “He slapped me in the face because I ate a lamb chop, which he had hidden in the icebox for his after‑theater, midnight lunch.

“’If you want lamb chops‑‑buy your own,’ my husband said”

Their mutual dissatisfaction with the bonds of matrimony became apparent on the third day following the nuptials, when Lugosi demanded her checkbook and key to her safe deposit vaults, Mrs. Lugosi explained.

“He told me that he was King; that in Hungary a wife and all she possessed were placed at the husband’s disposal; that, in effect, she was nothing but a servant

“Of course, I objected to this, and we quarreled.

“His table manners were terrible. He would break an apple in half and crowd one of the portions in his mouth, unable to speak or to swallow until he had chewed it up fine.

“He constantly used his fingers in place of a fork and was addicted to similar habits that simply frayed my nerves.”

Mrs. Lugosi, who fled from their San Francisco apartment while her husband was portraying his role in a leading Coast theatre, said the actual breaking point came when her husband elaborately furnished his own bedroom, afterward informing her if she didn’t care to equip her own, she could sleep on the floor.

As executrix of her former husband’s $2,500,000 estate, Mrs. Lugosi settled in her luxurious Riverside Hotel, Reno suite, said she was in no need of funds and expected none from her husband.

“I wish Miss Bow all the luck in the world,” she said. “However, I cannot see any happiness for her if she marries my husband unless he improves his manners.”

The Mirror’s reporting contains numerous inaccuracies—Lugosi was not a “count”; he and Bow were never engaged and he therefore did not “jilt” her for Beatrice; four years separate his divorce from Ilona von Montagh (his second not his first wife) and his meeting Clara Bow. Yet, the article contains many tantalizing truths as well—the timing and duration of the obscure Montagh marriage are correct; Lugosi’s imperious demands on his wife ring true, as does the simple fact that Lugosi and Bow were romantically involved. What of the remainder is truth or The Mirror’s creation is unknown. Beatrice’s only reliably reported comments came at the divorce hearing on December 9, 1929 in Reno. She testified that Lugosi was “sullen and morose and inhospitable to their guests… temperamental to the extreme…and had a violent temper.” Lugosi was not present (nor did attend any other of his divorce hearings). and Beatrice’s claims went uncontested. The final decree, on the grounds of incompatibility, was handed down the same day. The Associated Press picked up the story, but outside of San Francisco it hardly ran. The Chronicle gave the divorce front page coverage with the headline, “Wife of ‘Dracula’ Star Says Role Carried Too Far.”

Quite possibly, Lugosi and Weeks worked together towards a swift end to their marriage. Her complaint filing describes the minimum grounds for divorce; and is exactly what two people trying to escape an unwanted union would present to the court. Lugosi later maintained that he and Beatrice had remained friends, and even that Beatrice sought reconciliation.

In April 1930, Beatrice was still residing at the Mark Hopkins Hotel, but apparently still travelled as much as her health allowed. She died, age 34, in May 1931 in Colon, Panama. Three months before, the film Dracula had premiered, and made Bela Lugosi world famous. Beatrice’s death certificate gives cause of death, “oedema of brain” (ie, a swollen brain) could have been due to infection, accident or her own failing health. Colon is hardly reputed as a tourist destination or health spa. How or why she wound up in there a place is not known. A clue comes from Polly Alder’s autobiography, A House Is Not a Home. Alder calls Colon, “the last port of call, the bottom of the barrel.”

* * *

To order a copy of Frank J. Dello Stritto’s critically acclaimed book, A Quaint & Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore – The Mythology & History of Classic Horror Films, Please contact him directly at: fdellostritto@hotmail.com

—————————–

Related articles

Bela Lugosi’s Clara Bow Nude Painting Sells For $30,000 At Auction.

A Quaint And Curious Volume Of Forgotten Lore by Frank Dello Stritto

Three Tales – One Story by Frank J. Dello Stritto

Dracula’s Coffin: The Story of Bela Lugosi’s Steamer Trunk by Frank J. Dello Stritto

Mystery of the Gróf Tisza Istvan: Bela Lugosi Arrives in America by Frank J. Dello Stritto.

Ilona’s name is misquoted in this article from the Evening Telegram, February 19, 1921

Ilona’s name is misquoted in this article from the Evening Telegram, February 19, 1921