John Chartres Mather (Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

John Chartres Mather (Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

John Chartres Mather had been in theatre since age 12. Taking his lead from Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland musicals, the young man staged local revues in his native Edinburgh. After a year as stagehand in Dundee repertory, he took on London. Through the war years, he launched musical revues to entertain British troops. John also did tenures as stage director on the road and on the West End. By the late 1940s, still in his mid-20s, John was producing his own musical revues. John’s tastes in productions tended towards extravaganzas, and he always over-reached a bit, “flying before I could walk” as he described it. Musicals were expensive undertakings; they lost big when they failed and earned big when they succeeded. Fine Feathers temporarily made him rich. His labor of love, Out of This World, folded in previews, a devastating setback financially and personally. Musicals were John’s first love, but the expense and recent track records of the big productions he favored made them difficult to finance. John needed to get into something new. With his partners George Routledge and Gordon White, he formed Chartres Productions in early 1951 and produced Bela Lugosi’s British tour of Dracula.

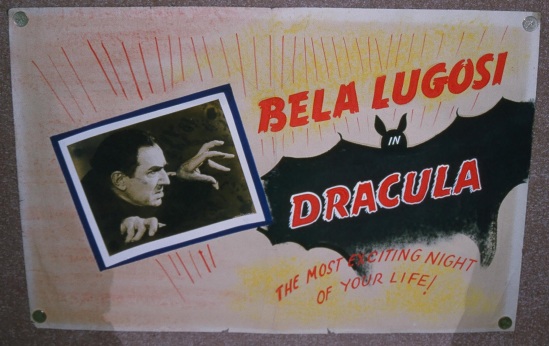

John’s mock-up of a poster for the tour

John’s mock-up of a poster for the tour

(Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

Frank J. Dello Stritto interviewed John Mather at his home in south England on August 8, 1999:

Frank Dello Stritto: How did you decide to produce Dracula?

John C. Mather: I was having drinks with a few friends in London. Charles Feldman, head of Famous Artists, was there. There were three big talent agencies at the time—William Morris, MCA and Famous Artists. Charlie had heard that Bela Lugosi’s agent in the US was trying to interest someone in Dracula. By coincidence, Gordon White had mentioned it to me also a few weeks or months before. So, that was when I first thought about it seriously.

FDS: How did that work—putting together a production?

JCM: First, I had to make sure I could book it. I took the idea to the theatre agents. The West End theatres wouldn’t even talk to me until it had toured. There were three big theatre circuits for the tours—the Stoll Circuit, Moss-Empire, Howard & Wyndham. They each had about 10 or so “Number 1” theatres around the country. Then there were “Number 2” and “Number 3” theatres in the smaller towns. You could make money even at the number 3s, since there wasn’t much else to do in those places. Deals with theatres ranged from 50/50 to 60/40 splits, depending on a lot of things: production, stars, publicity budget. Booking agents wanted to see my budget for publicity posters in detail: 300 double posters, 150 four-crowns, 6,000 throwaways, placards, etc. The plan was always to get into the West End. Early in the tour, I had a verbal agreement with the Garrick theatre: the production then playing there was expected to drop below its box office threshold soon. After 3 weeks below the limit, the theatre could give it a two week notice. Then “Dracula” could come in. Tour for 6 to 8 weeks and then into the Garrick Theatre—that was the plan. I had dates lined up for the tour, and would have cancelled them if the call came from the West End. It never did. I never intended to tour for 24 weeks.

*

John’s mock-up of a poster for the tour

John’s mock-up of a poster for the tour

(Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

*

FDS: Why were you interested in Dracula?

JCM: In 1951, Americans-in-the-flesh were in vogue. Danny Kaye had been coming over regularly, and there was a demand for more. I think that’s when Judy Garland started coming over as well. Just prior to Dracula, George Routledge did “fronting up” for a Jane Russell revue. And I knew I could pull Dracula together pretty quickly.

FDS: Fronting up?

JCM: Fronting up—supplying the supporting acts that come on before the star attraction.

FDS: What was your budget like?

JCM: I invested about £2,000. Bill Williams about £1,000, and £2,000 each from other backers. I don’t remember who they were. I think one of the backers was named “Burton,” in real estate or something like that. He was dating a “Renee” who was in some of my musical reviews. I just doesn’t remember their full names. So, about £7,000. For that I could get the show started and keep it on the road for as long as I had to.

FDS: What about Routledge & White?

JCM: They were my partners in Chartres Productions, but they never had much to do with Dracula. George Routledge liked the idea, as I recall, but he wasn’t interested in investing in it or working on it. Gordon White thought it was a terrible idea—didn’t think it would succeed at all. He thought we were crazy, but he handled the negotiations to contract Bela.

*

John’s rough idea for advance publicity for Dracula

John’s rough idea for advance publicity for Dracula

(Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

*

FDS: All the programs for Dracula mention Routledge & White very prominently.

JCM: Well, they were my partners, and we used the same office, so I put their names on the programs. But they really didn’t have much to do with it. Gordon White quit the business and worked with Jimmy Hanson when he set up the Hanson Trust. Gordon died a few years ago in California, a very wealthy man. George Routledge had some legal and money problems and left the business a few years after Dracula. He lives in Denmark now.

FDS: Was Lee Ephraim a backer?

JCM: No, he wasn’t. I knew Lee well, and his partner Betty Farmar. I had worked for Lee on Waltz Time and Lee had been a backer on Out Of This World.

FDS: How about Nigel Ballantine?

JCM: Oh, no! Nigel was in jail by then!

FDS: In jail?

JCM: He ran off with the leading lady and all the money from one of his productions, and got caught.

FDS: What was your impression of Bela?

JCM: I met Bela and Lillian when they landed in Southampton. Bela looked as if he were going to die. He always looked that way. Bela was very charming, very humble, not conceited in the least. For the first 2 or 3 days of rehearsals, he only walked through his part. I was wondering about cancelling the whole thing. On the third day, Dickie Eastham asked the cast to do their read-throughs in character. Bela stood straight and awed everyone. Bela had always looked like a tired old man—very gray, very old and bent, years older than his actual age. He spoke very slowly, softly and mumbled a bit. This all changed when he was onstage—the transformation was complete: he looked 40 again, erect and towering. When he was Dracula, he had this twinkle in his eye. He was so charming, and then so evil. It was magnificent.

* Lillian and Bela Lugosi arrive in England aboard the S.S. Mauretania

Lillian and Bela Lugosi arrive in England aboard the S.S. Mauretania

*

FDS: Tell me about your first meeting with Bela.

JCM: I think Dickie and me both went to Southampton to meet Bela and Lillian. I put them into a hired limousine and hurried ahead to London. I had the flat stocked with goodies, and a bottle of champagne waiting. I had made a reservation at Carlton Towers, a table by the window for 6:00. Lillian said “No, Bela’s tired and he’s going straight to bed.” We dined there later, several times, and it became a favorite of theirs.

FDS: I have been warned that you and Lillian didn’t always see eye to eye.

JCM: Oh, she was awful! Awful! She loathed me. It was mutual loathing from the first day.

FDS: Well, I must say that everyone else on the tour speaks well of her.

JCM: Really? Well, she was an extraordinary woman, but a pain-in-the-ass. She took notes through the rehearsals, and interfered. I had it out with her once. After that, she sat in the back of the stalls; but still kept those notes. Lillian looked tough and was a strong woman, physically. At dress rehearsal, a hamper was in the way. Lillian lifted it and set it on the table. I went and looked inside—it was filled with books and files. I was curious and nudged it to check its weight, and wondered if I could have lifted it. Lillian seemed desperately unhappy. I think she had a terrible inferiority complex. She had a strident voice, heavy Chicago accent. Nothing ever pleased her—in restaurants and the theatre, anywhere. She browbeat Bela, who just seemed to tune her out and accept it. She was bitter about how Bela was treated—Hollywood had once been at his feet, studios phoning constantly, but now they shunned him.

FDS: Again, the company members we’ve talked to have quite different memories of her. If anything, they think Bela controlled her life.

JCM: I think Lillian bullied Bela, a bit—treated him like a child. At dinner she did everything but cut his meat. She sent food back in restaurants. I think Bela was used to this, since he just munched away. She was always at the side of the stage—every night. Something was always wrong that she’d complain about.

(Authors’ Note: In follow-up interviews, I pressed Dickie Eastham on John Mather’s memories of Lillian. Dickie stands by his much more favorable memories of Lillian, but strongly confirms that John and Lillian simply never got along. “It was chemical,” Dickie told mes, “it started as soon as they met.” Lillian undoubtedly could be fiercely protective of Bela. John, as the producer of a tour that was not quite what she and Bela expected, saw a side of that affection that few others did.)

*

Bela Lugosi in John’s production of Dracula

Bela Lugosi in John’s production of Dracula

(Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

*

FDS: I have to ask you something directly. There has always been a persistent claim that Bela was never paid for the Dracula tour.

JCM: Oh, he was definitely paid. Everyone, every actor in every show I ever produced was paid. I treated Bela and Lillian well. I didn’t want them saying anything negative like that about me. I couldn’t survive long in this business with people saying I didn’t pay them.

FDS: Any special memories of Bela?

JCM: Bela was always marvelous, once you got to know him. At our first meeting in Southampton, I thought he looked so feeble and I really feared for the production, but he never let us down. I dined out with them often, especially during rehearsals in April. I always watched Bela’s intake of alcohol. I did that with all the stars of my shows. He never drank that much in front of me. Lillian saw that he didn’t. Before dinner, I would go to their flat on Chesham Road to pick them up. Once, while Lillian got ready, Bela sat me down on the sofa, and brought out a huge scrapbook of old clippings. They were from his days in Hungary. They were all in Hungarian of course, and I couldn’t read anything but Bela’s name in the headline. They were obvious rave reviews. Bela went through them one by one. It was very important to him, I think, for me to know about his days before Dracula.

FDS: Do you have any memories of the rehearsals.

JCM: The rehearsals started in bare rooms above the pub on Pont Street. For the second week, we moved to the Duke of York Theatre. It had a one-set play on at the time. So, we could rehearse during the day, and put the set back in place before the performance. It was a courtesy that theatres extended to productions in rehearsal. I was at some rehearsals, but only to observe. Dickie and I would meet afterwards to discuss how it was going. If there was any problem, I would talk to Bela about it over dinner. But things went smoothly enough.

FDS: How about the dress rehearsal?

JCM: That’s a different story. Things didn’t go well. The effects did not work. The smoke took seven seconds to get through the pipes. Too much smoke and the house was filled. Too little and it had no effect. Bela had to disappear in the smoke—no smoke and he was left standing there. It took forever to work out. Lighting effects were a bit difficult—but nothing compared to the musicals I had produced. Those were really complex. So, I thought Dracula would go pretty smoothly. But it didn’t. Strand Electric—that’s where I got the equipment from—was supposed to send a man down to Brighton for the week, but never did. I was very annoyed. We kept the cast until two in the morning, working through the lighting effects. We let the cast go to get some rest. The rest of the company stayed until eight in the morning. Dickie and I went to breakfast and commiserated. But we got them straight, and the opening went well. The reviews were fine.

*

Dracula opened at the Theatre Royal in Brighton on April 30th, 1951

Dracula opened at the Theatre Royal in Brighton on April 30th, 1951

(Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

*

FDS: You had your own lighting equipment? Wouldn’t the theatre have that?

JCM: Yes, we had our own. We had to. On tour, you never know what the theatres have. So, we had to able to do it ourselves.

FDS: How did the tour do?

JCM: Dracula had too high a weekly expense to make money on the road. I had to get it into the West End, and didn’t. So, I lost money. Not a lot. Some weeks, it made money, some weeks it didn’t. Dracula was not cheap to produce. There was Bela’s salary. There were nurses at every performance; so St. John’s Ambulance had to be paid a contribution. There were 3 or 4 musicians every week to play at the intermissions. We had long intermissions, and had to fill them with something.

FDS: How was the company to deal with?

JCM: It was a nice company—not much trouble, not many complaints. Whenever the tour was near London, I would catch the show to check on things. I’d circulate around the dressing rooms talking to everyone I could. It was a good cast. Most of the problems mentioned to me, I referred to Alfred Beale, so as not to usurp his authority.

FDS: So, Beale was in charge on the road?

JCM: Yes, he would call me every night to report on the box office and the performance. He was a good man and a good business director. He had a good heart. He’d be tough with the company when he had to be, but then he’d apologize and undo whatever good he had done. But he was a good manager and I was glad to have him.

*

Bela Lugosi, Arthur Hosking, Richard Butler and David Dawson in John’s production of Dracula (Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

Bela Lugosi, Arthur Hosking, Richard Butler and David Dawson in John’s production of Dracula (Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

*

FDS: The programs list a Douglas Bodkin as publicity manager. We’ve been looking for him. Do you have any memories of him?

JCM: Not really. He was the advance publicity man. He did all his work Mondays and Tuesdays—lining up the publicity, arranging for a few things. But I didn’t know him well then, and I’ve heard nothing about him since.

FDS: The programs also list a W. H. Williams as your co-producer. What about him?

JCM: Bill Williams was the head of Merton Park Studios. He was more of a backer than a producer, but I felt I owed him something, so I billed him as co-producer. Bill invested in Dracula and has also put money into Out of This World. He supplied the smoke machine and the bat that you’ve heard so much about. Honestly, I hadn’t heard any of the stories about them breaking down until I spoke to you. By the way, I do remember that my sister, Rosemary, attended a theatre garden party with Bela. For some reason, Lillian couldn’t go, so my sister went with him.

FDS: Theatre garden party?

JCM: There were theatre garden parties and movie garden parties. They would be held on large outdoor lawns. Shepperton Studios lot was a typical place. People would go and meet actors and actresses. Stars would sit at tables and sign autographs. Sometimes they would be driven to different sites through the day. For producers, they were a bit of a nuisance, but a good place to show off actors. Rank studios always paraded out its starlets. I remember I saw Honor Blackman and Joan Collins at these parties. You can speak to my sister about her day with Bela.

*

Bela Lugosi at the Sunday Pictorial Film Garden Party at Morden Hall Park in Surrey. (From the British Pathe newsreel Seeing Stars)

Bela Lugosi at the Sunday Pictorial Film Garden Party at Morden Hall Park in Surrey. (From the British Pathe newsreel Seeing Stars)

*

FDS: How close did you come to getting Dracula into the West End?

JCM: Very close. The Garrick wanted us after its current play closed, but that play—I forget what it was—hung on and on. I also had discussions with the Duke of York and The Ambassador, and they were very interested. If we could have kept the tour going, I would have gotten it into one of them.

FDS: Why did the tour end?

JCM: Touring is hard work, and I never planned that we would tour for six months. Late in the tour, I received a call from Alfred Beale, “I’m a bit worried about Bela,” he said, “He came on in Act III, and started with Act I dialogue.” I went and met with Bela, and realized how tired he was. You see, he always looked so tired offstage but was always so good on stage. I had just learned to ignore it, but he was really exhausted. We were discussing some details in his dressing room when Lillian came in. “It’s late,” she said. She took out some sort of kit, and gave Bela an injection. “You know, he’s diabetic.” I knew that wasn’t true. I had heard about some kind of injections, but didn’t think much about it, since Bela was always so good onstage.

*

The end of the road for Dracula in Britain, the Theatre Royal, Portsmouth (Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

The end of the road for Dracula in Britain, the Theatre Royal, Portsmouth (Courtesy of Andi Brooks)

*

FDS: Is that when you decided to end the tour?

JCM: No, but I didn’t quite know what to do. I still kept looking for bookings for the tour, and had lined up a few dates near Newcastle & Liverpool, but Lillian said, “Oh, don’t put us up there again.” She wanted to keep the travelling to a minimum. Two or three weeks later I visited Bela backstage in Derby. Lillian wasn’t there. I told Bela that we had to play those dates or not play at all. He looked at me a long time. “John, I can’t go on,” he said, “It’s taking too much out of me. Please finish it quickly.” I put up the closing notices that week.

FDS: But you played Portsmouth two weeks later.

JCM: Yes, I had already signed for that week, and I had to give the company two weeks notice. Those were the rules. Portsmouth was a bad week at the box office.

FDS: When was the last time you saw Bela?

JCM: I visited them after the tour ended, before he started filming the movie he made. He still looked very tired. I had no second thoughts. He sat in a chair and we just talked. He said he was glad the tour was over, but that he had enjoyed it. He told me some anecdotes from the tour, and we said goodbye. As I was leaving Lillian gave me a hug and thanked me. I was surprised that she did that. It was a side of her that I had never seen.

*

Iris Russell and Sonny Tufts in Shadow of a Man (1952)

Iris Russell and Sonny Tufts in Shadow of a Man (1952)

(Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

*

*John Mather lost some money on the Dracula tour, but a year later he tried the same formula with a tour of the mystery, Shadow of a Man, starring Sonny Tufts. The tour did fine until Tufts, battling a drinking problem, came onstage between acts, told the audience who-done-it, and then launched into his own stage act using a piano that was part of the set. The audience loved the surprise, the theatre management did not. Any performance on a British stage had to be approved by the censors beforehand, and such improvisation exposed to the theatre to legal action, especially if Tufts’ act contained any adult humor. Word spread quickly throughout the theatre chains, and the tour soon ended.

*

Patricia Laffan as the Devil Girl From Mars (1954)

Patricia Laffan as the Devil Girl From Mars (1954)

*

In London John worked for the Danziger brothers, producing 26 episodes of Mayfair Mysteries for Paramount. In the early days of television, many American shows were made in Britain due to the lower costs. John had 40 days to produce the entire series. Character actor Paul Douglas flew in for a single day from Los Angeles, filmed all 26 introductions and epilogues, and flew back without staying the night. Incredibly, filming completed almost two weeks early. The Danizigers thus had 10 days of paid studio space to use; launching John on his most enduring and infamous achievement. Devil Girl From Mars was written in a few days, as John telephoned around London for available actors and had the sets prepared. AtomAge, British suppliers of latex, the latest wonder material, cut him a good deal on the Devil Girl’s costume. Pat Laffan, in the title role, liked the feel of it and loved how it looked. John took screenwriting credit for Devil Girl From Mars, but in the chaos of low budget, tight schedule filmmaking, everyone did everything. A wonderfully awful movie of the type that only the 1950s could sire resulted. Like many early science fiction epics, Devil Girl From Mars’ clumsiness and naiveté gives it a charm that delights its fans and mortifies its detractors.

*

John with Anthony Newley (left) and Roger Moore (right) in October 1968 (Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

John with Anthony Newley (left) and Roger Moore (right) in October 1968 (Courtesy of Frank J. Dello Stritto)

*

In 1954, John established a talent agency in Rome, where American movie companies were doing lots of filming due to the low production costs. He ran John C. Mather International, Ltd. for many years, before selling out to the William Morris Agency. He then ran the London office of the Morris agency. In 1973, he returned to theatre production. His extravagant stage version of The Avengers featured terrific special effects, with a helicopter crashing onstage in the finale. Audiences loved it, but it closed in London after seven weeks—too expensive to turn a profit. Following his retirement from show business, John took up writing, and has published several novels to date. His as-yet unpublished autobiography, Hollywood on the Tiber, focuses on his days as a talent agent in Italy.

Related Pages

1951 British Dracula Tour – Newspaper Articles And Memorabilia

1951 British Dracula Tour – Exclusive Interviews With The Cast & Company